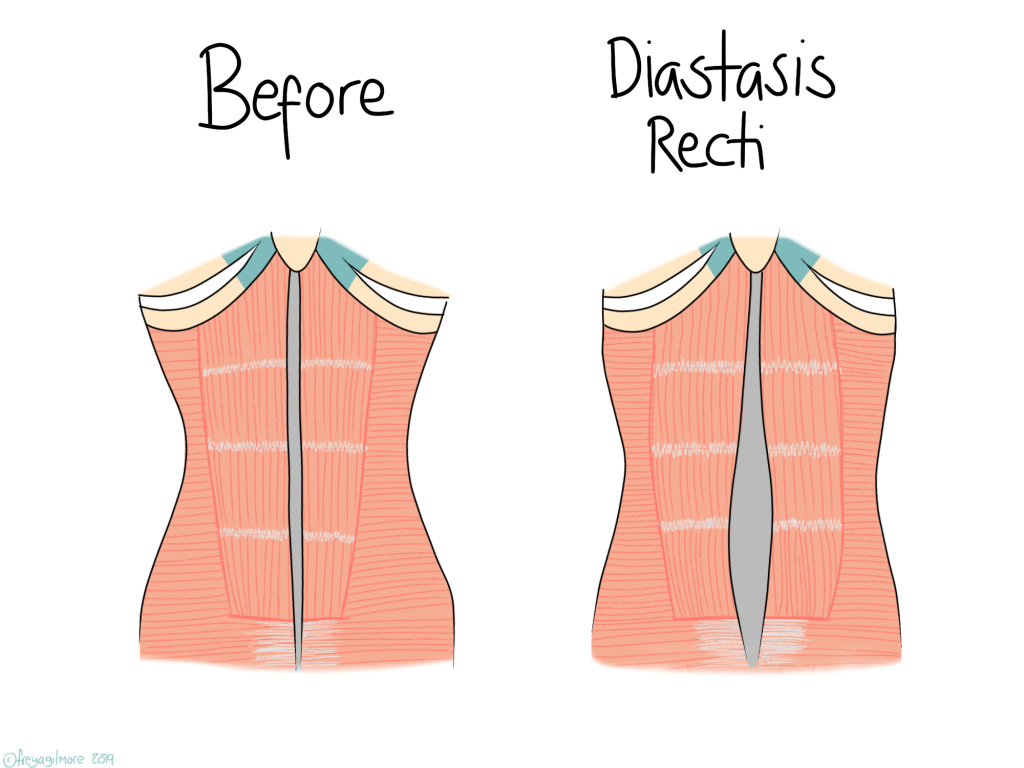

During pregnancy, the abdominal muscles have to come apart to make room for the bump. If they don’t knit back together after while the body heals post-partum, the patient can be diagnosed with diastasis recti. Diastasis means separation, and recti refers to the 6-pack muscles: rectus abdominus. Diastasis is not exclusive to women who have been pregnant, it can also occur in men, for example with obesity.

What happens in Diastasis Recti?

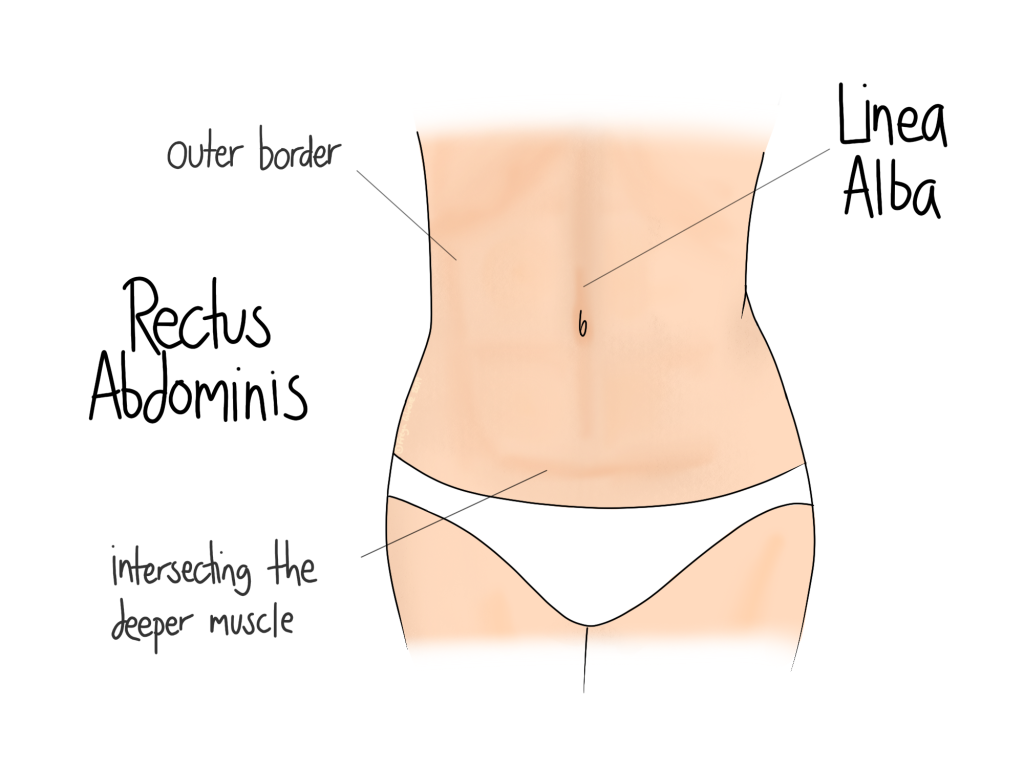

This is not a muscle tear! The body is prepared for this to happen. On some women there is a visible vertical dip in the middle of her abdomen. This is where the linea alba is: the line of connective tissue that sits between the two rectus abdominal muscles. It is the linea alba that thins and widens during diastasis- the muscles themselves don’t change. It is worth noting that a gap could be anywhere along the linea alba, above, below, or surrounding the belly button.

Annoyingly, I haven’t found any information that agrees on a clinical definition for diastasis recti. Anatomically, it is a separation of the rectus abdominus muscles. But for all full term pregnancies there will be a degree of this separation to make room for the baby. To say that all women have diastasis recti after pregnancy would be potentially fear mongering and not particularly useful. To give some rough numbers, I would not consider a patient to have diastasis recti until she is beyond 6 weeks post partum, and if the gap is more than two fingers wide.

Some salient points from the research papers:

- The abdominal muscles will separate to some degree in all full term pregnancies

- In some women, this separation can be seen as early as 21 weeks pregnant

- Up to 40% of women still have a gap between the muscles 6 months after giving birth

A bit more anatomy for those who are interested: the rectus abdominus (RA) is the top layer of the abdominal wall. The next layer down is the transversus abdominus (TA). The TA covers a broader area, and the fibres run horizontally, whereas the RA fibres run vertically. This means that the two muscles perform different movements, which we will bring up again later.

Do I have diastasis?

The NHS has a useful guide for self diagnosis and monitoring of diastasis:

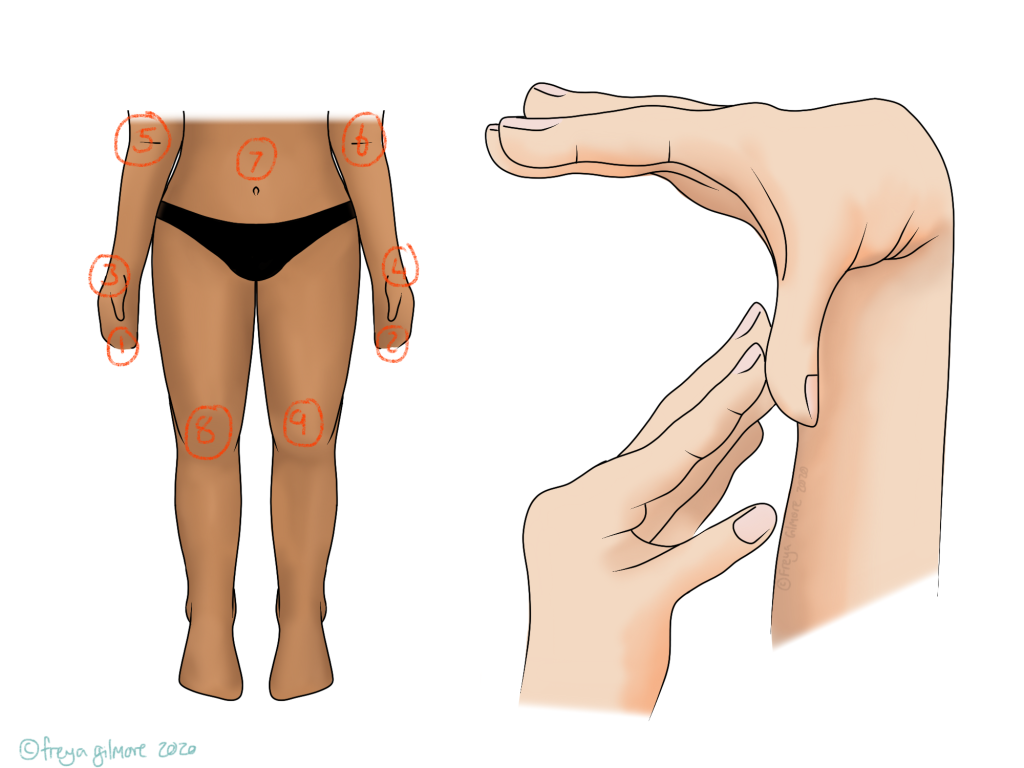

- Lie on your back with your legs bent and your feet flat on the floor.

- Raise your shoulders off the floor slightly and look down at your tummy.

- Using the tips of your fingers, feel between the edges of the muscles, above and below your belly button. See how many fingers you can fit into the gap between your muscles.

If you can fit two fingers or more into the gap anywhere in the centre of the abdomen (at any height between the ribcage and pelvis), it would generally be agreed that you have diastasis recti.

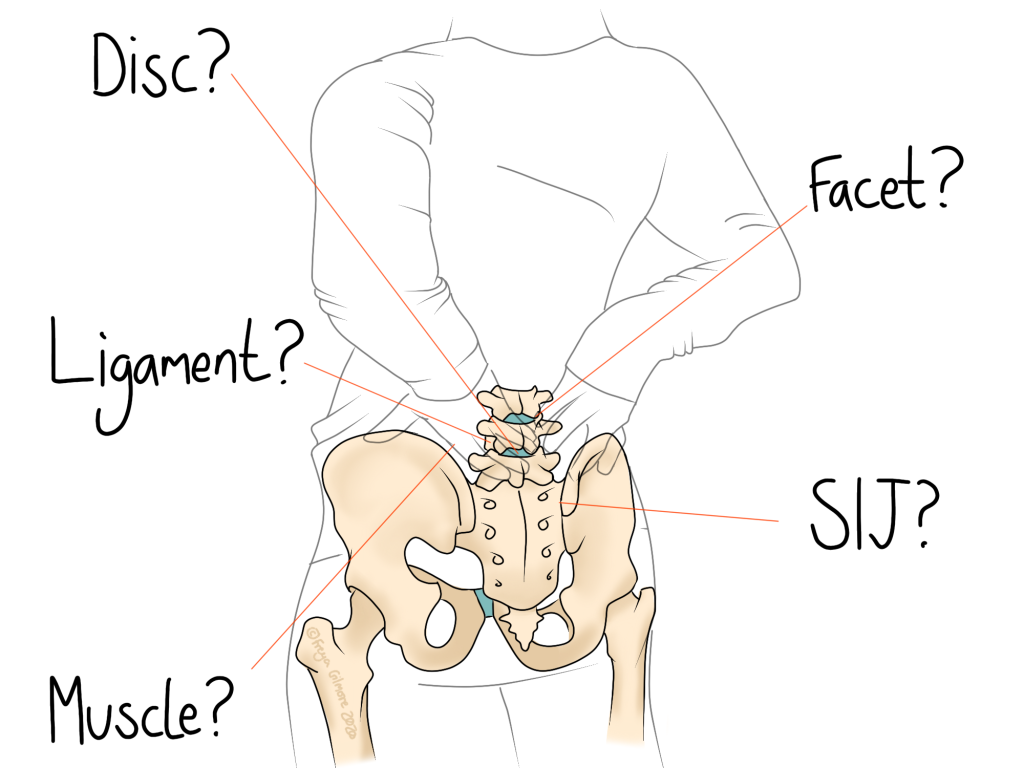

The NHS post goes on to suggest that diastasis is a risk factor for lower back pain. However looking through research, I found a higher-quality study that concluded there is no significant relationship between diastasis and lower back pain or incontinence, but another article to contradict it. The first paper in question recognised that the studies available are weak, so it starts to become clear why there is so little information out there for patients.

At this point it is worth saying that diastasis recti in itself does not equal dysfunction. If you have a small gap, feel no ill-effects and are happy with how it looks, you can carry on as normal. Another important message is that diastasis recti cannot be prevented in pregnancy, only managed. It is a natural response to a huge demand on the abdominal muscles, and although good abdominal strength may help with recovery, you can’t plank your way around a separation!

Plan A: exercise

Despite the contradicting information out there, we are sure of the basics enough to make a change. We’re dealing with muscles here, so the first plan is to strengthen them. I mentioned above that there are two different muscles involved, and they are responsible for different movement. So no one exercise is going to target them both effectively. (1), (2)

This will likely be a very individual plan and may be worth seeing a (specialist) personal trainer for. If you have diastasis recti, there will be a number of factors that set your limit for exercise. If you have had a caesarian, you may find that it takes longer to get into exercise than someone who didn’t have to heal after that major surgery. Likewise, if you had a tear or episiotomy, that may slow down your progress too. In any case, pay attention to your body and build up slowly.

The best reference I’ve found for putting all of this information into action is the website of Brianna Battles. Brianna is a coach for pregnant and post-partum women, and has had diastasis recti herself. I would absolutely recommend anyone looking at how to train post-baby to look at her e-book, especially for women with higher demands for their athleticism.

Barts Health Trust has a document listing a few good exercises to start with. Skip ahead to the exercises and don’t take any information from the start of the booklet with a pinch of salt. I have found no evidence to support a few of the bullet points in there.

I want to make it clear that this does not suggest diastasis can be prevented with prenatal exercise. It may give better chances of quicker healing or more complete reunion. The evidence is limited. But of course, there’s no harm in getting into good habits as early as possible.

Plan B: surgery

Not everyone will be able to get the results they want with exercise alone. This, again, is nothing to do with fitness or ability. Brianna, as mentioned above, made brilliant progress with her diastasis over two years. After putting in the work, she opted for an abdominoplasty. Taking the surgical route is totally up to the person having the surgery, and requires no justification to the public, but Brianna wrote a beautifully open blog post on the topic which I think will resonate well with people in a similar position.

Surgery is not failure.

Uncertainties

- There may or may not be a link between diastasis recti and higher incidence of lower back pain

- There may or may not be a link between a weaker pelvic floor and higher incidence of diastasis recti, or higher incidence of pelvic organ prolapse

- BMI, age, baby size, weight gain, and other factors may or may not be related to likelihood of developing diastasis recti.

Click here to make an appointment to assess and support your diastasis in MK or Buckingham