What is Osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis, that people sometimes just call “arthritis”. For simplicity’s sake we will only cover osteoarthritis (or OA for short) in this post. Often people just accept it as a by-product of getting older, but this isn’t really the case. Previously the tagline that’s gone with osteoarthritis is “wear and tear”, but more recently a new phrase has come into the foreground: “flare, tear, and repair”. This phrase emphasises that the condition isn’t a clear progressive one, but that it can be exacerbated and improved.

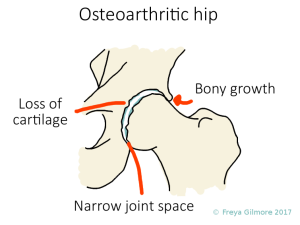

OA affects cartilaginous joints. The simple explanation is that the cartilage gets irritated and breaks down. One factor in this is that cartilaginous joints like to be moved throughout their whole range. This means that the whole surface of the joint will have some compression and some decompression, which is necessary to refresh the fluid in the joint and to essentially provide nutrition to the joint surface of cartilage. The mechanism of osteoarthritis is understood to be a breaking down of cartilage and less-than-perfect repair, with some bony growth coming in to replace cartilage. (UW Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine)

Does Osteopathy Work for Osteoarthritis?

Key findings from French et al’s 2017 paper included:

- Manual therapy may reduce pain for knee osteoarthritis in the short term

- Manual therapy may improve physical function for patients with knee osteoarthritis in the short term

- Improvements in pain and function following manual therapy may last up to six months for hip osteoarthritis

Ottawa’s clinical practice guidelines for OA, published in 2005, found that:

- Patients with arthritis tend to report a reduction of pain after exercise

- Manual therapy was significantly more effective than therapeutic exercise for patient global assessment, pain, stiffness, functional status, and range of movement after 5 weeks [of treatment]

- The Ottawa Panel has found evidence to recommend and support the use of therapeutic exercise (on their own or combined with manual therapy), especially strengthening exercises and general physical activity, for patients with OA, particularly for the management of pain and improvement of functional status.

What does treatment entail?

A good treatment plan for osteoarthritis will target the secondary effects as well as the joint surfaces. Prevention of further irritation is also important.

Cartilage and Muscle

We’ve established that cartilage likes to be used. Osteoarthritis can be a vicious cycle in that as a joint becomes arthritic and painful, you might avoid using it through its full range. This makes it worse! Often we find that a patient with osteoarthritis expects the pain, so tenses their muscles around the joint as they approach the painful movement. This can bring the irritated joint surfaces closer together (particularly in the case of the knee cap), causing more pain and irritation. Lenhart et al provide good evidence of this for the joint behind the kneecap. Your osteopath can help you break the cycle by gently working through the joint’s full range for you. This improves the availability of nutrition and waste removal in the joint, and helps to let your brain realise that the movement doesn’t have to be painful.

Swelling

Cartilage doesn’t have a good blood supply, so it relies on diffusion of nutrients and waste products to maintain a healthy state. Diffusion is easiest when there is a high concentration gradient: for example when the fluid is high in nutrients and the cartilage is lacking. So replenishment of this fluid will directly benefit the cartilage.

Swelling is a sign of inflammation. It’s more obvious in joints that sit close to the skin, like knee joints; but is less likely to affect the fingers. If you have an arthritic knee that is prone to swelling, then the joint will be surrounded by a fluid high in waste products. This means there’s less of a concentration gradient, so less waste can be removed from the joint. There are a few ways we can target excessive swelling:

- Manual drainage techniques: light pressure over the swollen area, towards larger vessels can give immediate results. By moving the more skin-deep fluid away from the area, the deeper swelling can begin to settle down too. This is not a cure, but it is a good starting point. (Vairo et al, 2009)

- Passive movement: an important part of treating osteoarthritis is getting the joint moving again. As above, this has the two-fold effect of refreshing the fluid around the cartilage and telling the brain that the movement doesn’t have to hurt.

- Active movement: when the joint is more comfortable, you’ll find that you can move the joint further through its full range. This has the benefit of compressing and decompressing more of the cartilage, with the bonus that the pumping action of muscles will further aid drainage.

Posture

After everything above about moving, it’s important to keep moving well to prevent a flare up. Continuing to use the joints through their full range will help to keep progression of the arthritis to a minimum. Not only will this benefit the joint in question, but it means that less compensation is required from other joints.

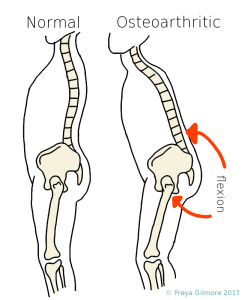

Someone with hip arthritis is likely to bend forward a bit to ease the pain. With this change in posture, the leg no longer needs to extend all the way back anymore when while walking. It’s not unusually for an OA hip to barely reach neutral. The joint is not taken through its whole range, so some areas of cartilage are not pumped to benefit from the joint fluid.

The cycle begins: the OA gets more progressive, the patient bend forwards more, and maybe takes shorter steps because it’s more comfortable. The local muscles respond to this, and the muscles on the front of the hip tighten, or shorten, because they are never stretched. Other areas start to adapt: the hunched posture of the lower back caused by the hip pain has to be corrected further up the spine, leading to achiness in the neck from craning the neck to look forward. (Truszczyńska 2017)

Summary

Osteoarthritis is a very common condition, but can be helped by bringing movement back to the joint. This can be achieved with a treatment plan from your osteopath involving hands on treatment and exercise. Reduction of pain and improvement of function have been proven to result from manual therapy. Improving function in the affected joint is important for reducing similar problems elsewhere as a direct result of compensation for the arthritic joint.

Click here to make an appointment for your osteoarthritis in Milton Keynes or Buckingham

References

Brosseau, L., Wells, G., Tugwell, P., Egan, M., Dubouloz, C., Casimiro, L., Robinson, V., Pelland, L., McGowan, J., Judd, M., et al (2005) Ottawa Panel Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Therapeutic Exercises and Manual Therapy in the Management of Osteoarthritis. Physical Therapy. 85 (9), pp. 907–971.

French, H., Brennan, A., White, B. and Cusack, T. (2011). Manual therapy for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee – A systematic review. Manual Therapy, 16(2), pp.109-117.

Lenhart, R., Smith, C., Vignos, M., Kaiser, J., Heiderscheit, B., Thelen, D. (2015).

Influence of Step Rate and Quadriceps Load Distribution on Patellofemoral Cartilage Contact Pressures during Running. Journal of Biomechanics, 48(11), pp.2871–2878.

Pinto D, e. (2017). Manual therapy, exercise therapy, or both, in addition to usual care, for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. 2: economic evaluation alongside a ran… – PubMed – NCBI . [online] Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23811491 [Accessed 10 Nov. 2017].

Truszczyńska A, e. (2017). Characteristics of selected parameters of body posture in patients with hip osteoarthritis. – PubMed – NCBI . [online] Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25058110 [Accessed 13 Nov. 2017].

UW Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, Seattle. (2012). Joints. [online] Available at: http://www.orthop.washington.edu/?q=patient-care/articles/arthritis/joints.html [Accessed 12 Nov. 2017].

Vairo, G., Miller, S., Rier, N. and Uckley, W. (2009). Systematic Review of Efficacy for Manual Lymphatic Drainage Techniques in Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation: An Evidence-Based Practice Approach. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 17(3), pp.80E-89E.